Continued from Part III, Part II and Part I.

Sorry this update took so long. This update is also a bit longer and has a little less guidance as it will simply require you to make use of some of the previous lessons to build your C code.

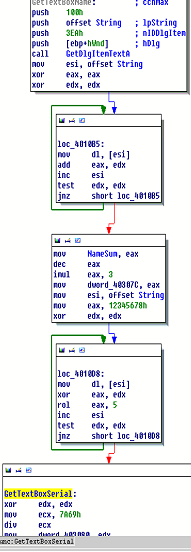

Let’s get to work on the rest of the key generation algorithm. First off, remember we have to call subChangeQWORD() four times and skip every 9th letter. The disassembly at 0x40111A shows this happening but it’s inlined instead of looped. The programmer wrote this in straight assembly but this may have been written as a loop that was unwrapped by the assembler to improve performance at the cost of a larger binary.

Anywho, here’s our new main() that will operate on the full 35-character serial instead of just the one segment we did previously:

int main(void)

{

const int iterations = 4;

char serial[35] = "serialnumbergoesherenowandstuffyay!";

char substring[9];

int offset = 0;

int i;

//printf("%s is %x\n", stringQWORD, subChangeQWORD("serialnum"));

//Loop is inlined at 0x40111A

for(i = 0; i < iterations; i++)

{

strncpy(substring, serial+offset, 8);

substring[8] = '\0';

printf("%s:\n", substring);

offset += 9;

subChangeQWORD((char *)substring);

}

return 0;

}Well, that was quite a diversion. Back in Part I we’d started with the code just before this, labeled GetTextBoxSerial.

We renamed a value to NameSum and then just moved on to see what was going on with the serial. Well, now it’s time to get back to that and figure out what’s going on with the username. Notice that between those two loops, there are seven lines of code and two of them change EAX before saving it off somewhere. These are values being saved for later so they should be renamed so we notice them when they’re used later. Ditto for what IDA has just called “String” here. We know “String” is the username value from the dialog box.

I’m not always consistent on this (and I really should be) but I will often use Hungarian notation for renaming variables in disassembly; it’s just easier to keep track of things. So, NameSum -> szUsernameSummed and dword_40307C -> szUsernameMultiplied. (We’re not renaming “String” here because, if you look further down in the code, you’ll see that the same memory location is re-used for the serial number; it’s just a placeholder for parameters.)

So here’s where IDA’s graph view can sometimes be deceiving. Take a look at the first several lines in the location we’ve labeled GetTextBoxSerial. After more operations on register values that are still related to the username, EAX and EDX are saved off to memory. At first glance, it would have been easy to just gloss over this, assuming it’s part of the serial number operations.

Let’s rename those variables as well, to ensure we know it’s still operating on the username: dword_403080->szUsernameDivided and dword_403084->szUsernameANDed. Also, be aware that szUsernameDivided was modified based on the ROL’d value of EAX in the previous loop: div ecx divides ECX by the value in EAX and stores the value in EDX, which is then saved off to the memory location we just renamed.

Okay, pause for a second. Have you noticed anything about the values derived from our username and serial? Each of them leads to four distinct values saved off into memory. We’ve just renamed the values resulting from the username alterations. Take a look at GetTextBoxSerial and notice that after each call to subChangeQWORD, the result is saved. Time to rename a few more things: I just use szSerialNum_alt[x] where [x] is consecutive 1-4 (alt as in altered).

As is often seen in software serials, the serial is probably derived from the username so we can expect to see each string’s four values involved in a mathematical operation with the other string’s values. Looking a bit further down, at 0x40116B, you’ll notice several calls to some other functions we haven’t looked at yet. There are also several JNZ instructions based on the checking of some register’s value. Look a bit below those jumps to see the call to MessageBoxA for a correct serial. If we were simply interested in cracking this, we could just change those JNZ instructions to NOPs and every username/serial combo would work.

Our goal, however, is to write a keygen. Let’s take a look at sub_4011F1:

sub_4011F1 proc near

var_10= byte ptr -10h

var_8= byte ptr -8

arg_0= dword ptr 8

arg_4= dword ptr 0Ch

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

add esp, 0FFFFFFF0h

pusha

mov edi, [ebp+arg_0]

mov esi, [ebp+arg_4]

lea ebx, [ebp+var_8]

lea ecx, [ebp+var_10]

push esi

push esi

push ebx

call sub_40128A

push offset szSerialNum_alt1

push esi

push ecx

call sub_40128A

push ecx

push ebx

push edi

call sub_401269

push offset szSerialNum_alt3

push edi

push edi

call sub_401269

popa

leave

retn 8

sub_4011F1 endpSo, it’s a function with two parameters that calls two other functions, twice each, consecutively. The first call to each function passes as arguments some of the arguments sub_4011F1* got from *DialogFunc and/or a couple local variables. The second call passes some of those arguments again (though they could have been modified by the called function) as well as parts of our serial.

Essentially, this function doesn’t need to exist as a separate function but let’s build out a skeleton for good measure. We can combine it with main() later if we want to. If you look back at IDA’s graph view, you can see that this could probably just be inlined in a loop. It’s easier to just do one thing at a time:

int sub_4011F1(int arg_0, int arg_4)

{

int edi = arg_0; //mov edi, [ebp+arg_0]

int esi = arg_4; //mov esi, [ebp+arg_4]

//char ebx; //lea ebx, [ebp+var_8]

//char ecx; //lea ecx, [ebp+var_10]

int * ebx; //lea ebx, [ebp+var_8]

int * ecx; //lea ecx, [ebp+var_10

sub_40128A(ebx, esi, esi);

sub_40128A(ecx, esi, szSerialNum_alt1);

sub_401269(edi, ebx, ecx);

sub_401269(edi, edi, szSerialNum_alt3);

}Looking ahead in the, we can see that the arguments being passed into sub_40128A and sub_401269 are likely ints, which is why I went back and commented out the chars in favor of int pointers. Let’s add function declarations for those other functions.

We’ll also need to adjust the main() function so that subChangeQWORD()’s returned value is saved in one of the szSerialNum_alt variables. I just used a switch based on the iterations variable:

for(i = 0; i < iterations; i++)

{

strncpy(substring, serial+offset, 8);

substring[8] = '\0';

printf("%s:\n", substring);

offset += 9;

switch(iterations)

{

case 1:

szSerialNum_alt1 = subChangeQWORD((char *)substring);

break;

case 2:

szSerialNum_alt2 = subChangeQWORD((char *)substring);

break;

case 3:

szSerialNum_alt3 = subChangeQWORD((char *)substring);

break;

case 4:

szSerialNum_alt4 = subChangeQWORD((char *)substring);

break;

}

}Those other two functions need to be written as well. Notice at the very beginning and end of the function the instructions pusha, and popa. Right off the bat, this tells us that the register values are irrelevant at the end of this function. However, the other catch to look out for is saving data to memory, like the two mov statements that store values in [edi] and [edi+4]. Keep these in mind as they’re essentially serving as pointers for variables.

Now it’s time to get cracking on that sub_40128A(). If you’re a math nerd, this function may bear a resemblence to the formula seen in the strings listing. Since that was covered in another solution, we’ll ignore that and just go about this without the benefit of recognizing the definition of the Multiplication of Complex Numbers in x86 assembly.

Here’s the code from sub_40128A() (sans preamble and cleanup):

mov esi, [ebp+arg_4]

mov ebx, [ebp+arg_8]

mov edi, [ebp+arg_0]

mov edx, [esi]

mov eax, [ebx]

imul edx, eax

mov eax, [esi+4]

mov ecx, [ebx+4]

imul eax, ecx

sub edx, eax

mov [edi], edx

mov edx, [esi]

mov eax, [ebx+4]

imul edx, eax

mov eax, [esi+4]

mov ecx, [ebx]

imul eax, ecx

add edx, eax

mov [edi+4], edxThis is pertty simple code so let’s just walk through it quickly. Those first three lines are just moving the three parameters into registers. The next two lines tell you that arg_4 and arg_8 are pointers. The next line just multiplies them together.

Next up, we’re getting two more numbers from memory, just offset by +4 from the pointers we already have and multiplying them together too. Then, subtract the result from the previous result and save that final result.

The last few operations are similar. Get some numbers, multiply them together in pairs but add those results this time. The primary thing to take note of, if you can follow which registers are storing what where, is that this second pair of imul operations is operating on the same numbers as before but multiplying them in a different order. Then the last thing before the function cleans up is to save this result right next to the previous one in memory.

The asm code used three parameters since it was operating on pointers, two pointers to cover the four integer values and one to provide a memory location in which to save the resuls. It’ll be easier for us to just use integers and return an array/pointer. However, this function is called from the one at 0x4011F1 so we’ll have to go back and fix the parameters used in those calls. For now, we can just comment them out until we decide whether to keep sub_4011F1() or not.

Here’s the entirety of algorithm.c up to this point. You can uncomment those first few lines in main() to test our new function if you like:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

unsigned int subChangeQWORD(char *);

int sub_4011F1(int arg_0, int arg_4);

void sub_40128A(int a, int b, int c, int d, int * results);

void sub_401269(int a, int b, int c, int d, int * results);

unsigned int szSerialNum_alt1, szSerialNum_alt2, szSerialNum_alt3, szSerialNum_alt4;

int main(void)

{

/*

int * results = malloc(sizeof(int)*2);

sub_40128A(2, 3, 4, 5, results);

printf("results[1] is %d\nresults[2] is %d\n", results[1], results[2]);

return 0;

*/

unsigned int szSerialNum_alt1;

unsigned int szSerialNum_alt2;

unsigned int szSerialNum_alt3;

unsigned int szSerialNum_alt4;

const int iterations = 4;

char serial[] = "serialnumbergoesherenowandstuffyay!";

char substring[9];

int offset = 0;

int i;

//printf("%s is %x\n", stringQWORD, subChangeQWORD("serialnum"));

//Loop is inlined at 0x40111A

for(i = 0; i < iterations; i++)

{

strncpy(substring, serial+offset, 8);

substring[8] = '\0';

printf("%s:\n", substring);

offset += 9;

switch(iterations)

{

case 1:

szSerialNum_alt1 = subChangeQWORD((char *)substring);

break;

case 2:

szSerialNum_alt2 = subChangeQWORD((char *)substring);

break;

case 3:

szSerialNum_alt3 = subChangeQWORD((char *)substring);

break;

case 4:

szSerialNum_alt4 = subChangeQWORD((char *)substring);

break;

}

}

return 0;

}

int sub_4011F1(int arg_0, int arg_4)

{

int edi = arg_0; //mov edi, [ebp+arg_0]

int esi = arg_4; //mov esi, [ebp+arg_4]

char ebx; //lea ebx, [ebp+var_8]

char ecx; //lea ecx, [ebp+var_10]

//sub_40128A(ebx, esi, esi);

//sub_40128A(ecx, esi, szSerialNum_alt1);

//sub_401269(edi, ebx, ecx);

//sub_401269(edi, edi, szSerialNum_alt3);

}

void sub_40128A(int a, int b, int c, int d, int * results)

{

int x, y, ans1, ans2;

x = a * c;

y = b * d;

ans1 = x - y;

x = a * d;

y = b * c;

ans2 = x + y;

results[0] = ans1;

results[1] = ans2;

}

unsigned int subChangeQWORD(char * stringQWORD)

{

const int strlen = 8; //[0x4012CD] mov ecx, 8

const int dlSub = 48; //[0x4012DB] sub dl, 0x30

const int dlCmp = 10; //[0x4012DE] cmp dl, 0x0A

const int dlCmpMaybe = 7; //[0x4012E3] sub dl, 0x7

const int eaxSHL = 4; //[0x4012E6] shl eax, 0x4

unsigned int eax = 0; //[0x4012C9] xor eax, eax

//unsigned int edx = 0; //[0x4012CB] xor edx, edx

int i; //Depending on your compiler, this may be embedded in the for loop instead.

for(i = 0; i < strlen; i++) //since we start at 0, i<strlen will get us through all 8 chars

{

unsigned int dl = (unsigned int)stringQWORD[i]; //[0x4012D5] mov dl, [esi]

printf("dl: %c\t", dl);

dl -= dlSub; //[0x4012DB] sub dl, 0x30

printf("dl - 48: %c\t", dl);

if(dl == dlCmp) //[0x4012DE] cmp dl, 0x0A

{

printf("Break!\n");

break;

}

dl -= dlCmpMaybe; //[0x4012E3] sub dl, 0x7

printf("dl - 7: %c\t", dl);

printf("eax: 0x%08x\t\t", eax);

eax = eax << eaxSHL; //[0x4012E6] shl eax, 0x4

printf("eax << 4: 0x%08x\t", eax);

eax |= dl; //[0x4012E9] or eax, edx

printf("eax |= dl: 0x%08x\n", eax);

printf("---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------\n");

}

return eax; //[0x4012F3] mov eax, [ebp+stringQWORD]

}Alrighty, so what’s next? How about that other function doing some math…

void sub_401269(int a, int b, int c, int d, int * results)

{

results[0] = a + c;

results[1] = b + d;

}Well that was simple. So, we’ve got two functions that require four arguments. Well, if you think back to a little piece in Part II, you’ll see where those areguments are coming from. It’s the username! We didn’t even bother to code that out. Go back to Part II and review the bit of code where we named a value NameSum (around 0x4010B5).

I called this function GetNameValues(). The code below is not commented to follow the assembly as there is nothing particular complicated about it. I do recommend you attempt to create this function yourself and just return here for reference. There are several gotchas you’re more likely to learn about and recognize when you get stuck on them.

If you do try to do this on your own, you can compare your function’s results against mine. For “username” as the char * name parameter, results should look like this:

results[0] = 00000360

results[1] = 00000a1d

results[2] = 00005c29

results[3] = 000004e1void GetNameValues(char * name, int * results)

{

int len = strlen(name);

int nameSum = 0;

for(int c = 0; c < len; c++)

{

nameSum += (int)name[c];

}

int nameMul = (nameSum - 1);

nameMul *= 3;

unsigned int nameShift = 0x12345678;

for(int c = 0; c <= len; c++)

{

//printf("nameShift: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

nameShift ^= name[c];

//printf(" XOR: 0x%x (nameShift ^ \'%c\' [0x%x])\n", nameShift, name[c], name[c]);

//nameShift = (nameShift << 1) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 1));

//printf(" ROL: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//nameShift = (nameShift << 1) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 1));

//printf(" ROL: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//nameShift = (nameShift << 1) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 1));

//printf(" ROL: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//nameShift = (nameShift << 1) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 1));

//printf(" ROL: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//nameShift = (nameShift << 1) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 1));

//printf(" ROL: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//printf("ROL(5): 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//printf("-------------------------------------------\n");

nameShift = (nameShift << 5) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 5));

}

int quo = nameShift;

nameShift %= (unsigned int)0x7a69;

quo /= (unsigned int)0x7a69;

int nameAnd = quo & 0x0FFF;

results[0] = nameSum;

results[1] = nameMul;

results[2] = nameShift;

results[3] = nameAnd;

}We’re almost done! Now, all we have to do is tie a couple functions together to get the actual serial number. Looking at the code, you should be able to see which functions we’ve created can just be dropped and which we’re using.

For reference, the serial number generated for “username” is:

00005f89-00000efe-0105b2e3-03b48205Again, I recommend you attempt to find this all on your own by following the code. Immediately after the section that you used to create the above function, you’ll have all the information you need to complete our keygen.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void GetNameValues(char * name, int * results);

void sub_40128A(unsigned int a, unsigned int b, unsigned int c, unsigned int d, unsigned int * results);

void sub_401269(unsigned int a, unsigned int b, unsigned int c, unsigned int d, unsigned int * results);

int main(void)

{

char username[] = "username";

unsigned int * NamesValues;

unsigned int * AddValues;

unsigned int * MultValues;

unsigned int * Serial;

NamesValues = malloc(4 * sizeof(int));

AddValues = malloc(2 * sizeof(int));

MultValues = malloc(2 * sizeof(int));

Serial = malloc(4 * sizeof(int));

GetNameValues(username, NamesValues);

sub_401269(NamesValues[0], NamesValues[1], NamesValues[2], NamesValues[3], AddValues);

sub_40128A(NamesValues[0], NamesValues[1], NamesValues[2], NamesValues[3], MultValues);

Serial[0] = AddValues[0];

Serial[1] = AddValues[1];

Serial[2] = MultValues[0];

Serial[3] = MultValues[1];

printf("%08x-%08x-%08x-%08x\n\n", Serial[0], Serial[1], Serial[2], Serial[3]);

return 0;

}

void sub_40128A(unsigned int a, unsigned int b, unsigned int c, unsigned int d, unsigned int * results)

{

unsigned int x, y, ans1, ans2;

x = a * c;

y = b * d;

ans1 = x - y;

x = a * d;

y = b * c;

ans2 = x + y;

results[0] = ans1;

results[1] = ans2;

}

void sub_401269(unsigned int a, unsigned int b, unsigned int c, unsigned int d, unsigned int * results)

{

results[0] = a + c;

results[1] = b + d;

}

void GetNameValues(char * name, int * results)

{

int len = strlen(name);

int nameSum = 0;

for(int c = 0; c < len; c++)

{

nameSum += (int)name[c];

}

int nameMul = (nameSum - 1);

nameMul *= 3;

unsigned int nameShift = 0x12345678;

for(int c = 0; c <= len; c++)

{

//printf("nameShift: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

nameShift ^= name[c];

//printf(" XOR: 0x%x (nameShift ^ \'%c\' [0x%x])\n", nameShift, name[c], name[c]);

//nameShift = (nameShift << 1) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 1));

//printf(" ROL: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//nameShift = (nameShift << 1) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 1));

//printf(" ROL: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//nameShift = (nameShift << 1) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 1));

//printf(" ROL: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//nameShift = (nameShift << 1) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 1));

//printf(" ROL: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//nameShift = (nameShift << 1) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 1));

//printf(" ROL: 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//printf("ROL(5): 0x%x\n", nameShift);

//printf("-------------------------------------------\n");

nameShift = (nameShift << 5) | (nameShift >> (sizeof(unsigned int) * 8 - 5));

}

int quo = nameShift;

nameShift %= (unsigned int)0x7a69;

quo /= (unsigned int)0x7a69;

int nameAnd = quo & 0x0FFF;

results[0] = nameSum;

results[1] = nameMul;

results[2] = nameShift;

results[3] = nameAnd;

}It’s a bit anticlimactic, but that’s it! We’re done!