Notice there’s another loop, so we’re not done messing with the Name field. Rather than sit and watch this, set a breakpoint at the DIV instruction, three lines past the end of the loop and let it run.

mov dl, byte ptr ds:[esi] ; loop start

xor eax, edx ; loop body #1

rol eax, 5 ; loop body #1

inc esi ; loop counter increment

test edx, edx ; loop condition (check for null)

jnz short Crackme.004010D8 ; loop conditional jump

xor edx, edx

mov ecx, 7A69

div ecx

mov dword ptr ds:[Crackme.403080], edx

and eax, 0x00000FFF

mov dword ptr ds:[Crackme.403084], eaxHere’s our register values before the DIV:

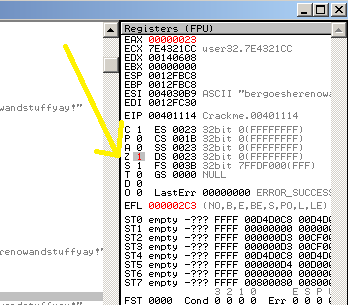

EAX 0xD0E6C672

ECX 0x00007A69

EDX 0x00000000

EBX 0x00000000

ESP 0x0012FBC8

EBP 0x0012FBC8

ESI 0x004030B9 Crackme.004030B9

EDI 0x0012FC30

EIP 0x004010EB Crackme.004010EBThe DIV instruction will divide EDX:EAX (as in, make it one long 64-bit number) by the specified operand, ECX in this case. The result is put in EAX (quotient) and EDX (remainder).

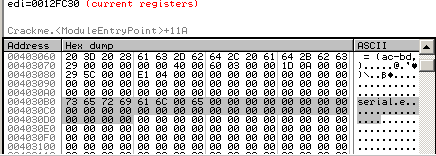

In the next couple lines, it stores the results (after messing with EAX again) and then retrieves the serial. Notice that OllyDbg still shows variable values for “username”. This is simply because the program is reusing the old variables. Afterwards, it fills in the current values.

push 24 ; /MaxCount = 36.

push offset Crackme.004030B0 ; |String = "serial"

push 3EB ; |ItemID = 1003.

push dword ptr ss:[arg.1] ; |hDialog => [ARG.1]

call <jmp.&user32.GetDlgItemTextA> ; \USER32.GetDlgItemTextA

cmp eax, 23

jne Crackme.004011D7It checks that the serial is exactly 35 characters. If not, it jumps directly to ShowDlgWrong. For us, that’s all she wrote. You can do one of two things here:

- Just hit run, let it fail and type in a new serial.

- Edit the memory to be a string of the proper length.

For #2, look at the memory dump beneath the disassembly window. If you don’t see “serial” in there now, then right-click on the text in the dissassembly and choose Follow in Dump»Immediate Constant. Then look below and click-drag to select 35 characters, which is just two rows (16x2), plus three characters. Remember that GetDlgItemTextA returns the length of the string not counting the null terminator.

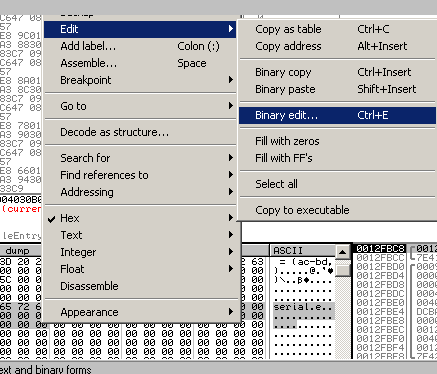

Right-click and choose Binary Edit.

In the binary editor, type out enough characters to fill the entire value.

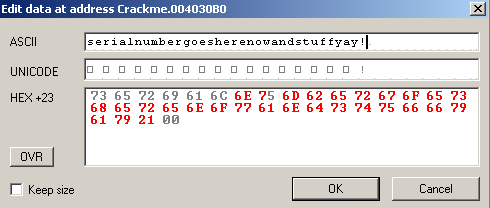

Don’t forget you’ll need to update EAX as well. It currently reads 0x6 but needs to read 0x23. This is just a matter of double-clicking on its value in the registers window. Last, if you’re like me and accidentally stepped over the CMP instruction already (and are unable to change EIP in the debugger), change ZF to 1 for true so the JNE isn’t taken. You’ll find ZF labeled ‘Z’ just below the general purpose registers with the other EFLAGS.

Now we’re getting into some kinda fun stuff. First, it moves the address of our serial into EDI and then replaces the 9th character with 0x0 (remember that this is zero-indexed).

call <jmp.&user32.GetDlgItemTextA> ; \USER32.GetDlgItemTextA

cmp eax, 23

jne Crackme.004011D7

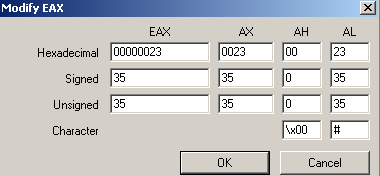

mov edi, offset Crackme.004030B0 ; ASCII "serialnumber"

mov byte ptr ds:[edi+8], 0OllyDbg updates the variable analysis properly. Putting a 0x0 is equivalent to putting a ‘/0’ (null terminator) so, in memory, OllyDbg sees two separate strings: “serialnu” and “bergoesherenowandstuffyay!”. The ‘m’ is gone.

push edi ; /Arg1 = ASCII "serialnu"

call Crackme.004012C5 ; \Crackme.004012C5That first string now goes off to that function, 0x004012C5. You can right-click on it in OllyDbg and hit “Follow” to see what that looks like or just pull it up in IDA. I prefer IDA right now, so we can get a bird’s eye view of the entire function. In IDA, it’s called “sub_4012C5”.

Right off the bat, you should notice two things:

- There’s a loop, likely for some sort of encoding, considering where we are in the code.

- That mov ecx, 8 line. ECX is often used as an incrementer for loops. The last two lines in the loop confirm this. It’s set to 8, the length of our string sans the ‘/0’.

The first thing I like to do when exploring a new function, is add comments for values I recognize and/or rename variables and sections. For example, arg_0 becomes stringQWORD. At first, I called it serialFirstQWORD before realizing that this function might be reused on the not-first-QWORD. To check on that, I hit the spacebar to go to IDA’s text view, select the first line of the function and hit ‘x’. This shows me multiple cross-references, so it’s used for other parts of the serial too.

Remember, comments should be input with ‘:’ not ‘;’, unless you want them repeating. You could put a repeating comment on the call to this function so everywhere it’s called, you see the same note.

Since this is such a small program, and I often end up having to go days without viewing the code because I get busy, I usually check the box to add my renamed locations to the Names listing. I also try to label them consistently (Lbl_ prefix or something) so I can sort the Names window and find them all in once place.

Here’s my commented/updated code from that function:

subChangeQWORD proc near

stringQWORD = dword ptr 8

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

pusha

xor eax, eax

xor edx, edx

mov ecx, 8 ; length of string

mov esi, [ebp+stringQWORD]

updateCharLoop:

mov dl, [esi] ; get first char

test dl, dl ; check for /0

jz short Lbl_allDone

sub dl, 30h

cmp dl, 0Ah

jb short Lbl_skipSubSeven

sub dl, 7

Lbl_skipSubSeven:

shl eax, 4

or eax, edx

inc esi

dec ecx

jnz short updateCharLoop

Lbl_allDone:

mov [ebp+stringQWORD], eax

popa

mov eax, [ebp+stringQWORD] ; put encoded string in EAX

leave

retn 4Now that we know what’s going on, let’s get back to OllyDbg and just step over this function. Take a look at EAX after the function returns. That’s the encoded result of “serialnu”. That gets stored back in memory, then EDI is incremented by 9. It’s being used as our array indexor so we’re moving on to the next part of the string.

mov dword ptr ds:[Crackme.40308C], eax

add edi, 9

mov byte ptr ds:[edi+8], 0

push edi

call Crackme.004012C5

mov dword ptr ds:[Crackme.403090], eax

add edi, 9

mov byte ptr ds:[edi+8], 0

push edi

call Crackme.004012C5

mov dword ptr ds:[Crackme.403094], eax

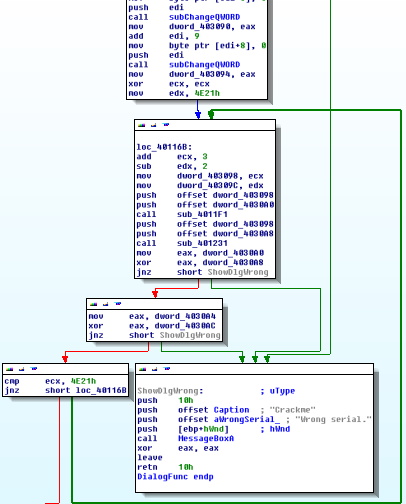

xor ecx, ecx

mov edx, 4E21It just does the same thing over and over again. Now we can see why it had to be 35 characters long. After converting three characters to nulls, that leaves four 8-byte strings, which go through the algorithm and come out half that size:

7E B7 B2 EF F1 AF B3 BF 7D 2B 7C BF EA 2E FF FE

serialnu bergoesh renowand tuffyay!But wait! There’s more!

So, it’s clearing ECX, putting 0x4e21 in EDX and then doing a bunch of craziness and calling more functions. It then, eventually, expects ECX to equal 0x4e21. If it doesn’t, it goes back through the craziness again.

Note that the craziness (AKA loc_40116B) begins by adding 3 to ECX. A quick look at the other two functions shows that they begin and end with PUSHA and POPA, meaning this loop must execute 6667 times (0x4e21 / 0x3 = 0x1a0b = 6667d).

We’ll take a look at these encoding functions next. Patching the EXE to simply ‘let us in’ is easy enough but we want to duplicate/reverse the algorithm and make a “key generator.”